- Binbirdirek Mah. Klod Farer Cad. Güven Apartmanı No:2/302 Fatih/İstanbul, Turkey

- Open 08:00-22:00: Monday - Sunday

- drop us an email info@istanbulguideservices.com

- 24/7 service +90 555 6022454

tags:

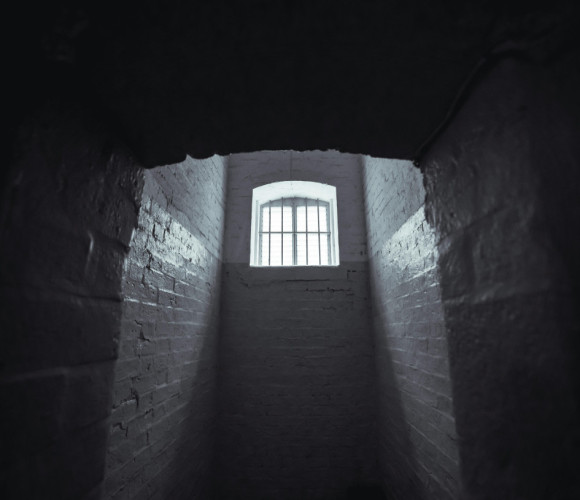

Life in the Cage

In the shadowed corridors of power that wound through the Ottoman palace, the fate of an empire often hung in the balance of succession politics. The sons of sultans lived lives of stark contrast—from battlefield commanders to prisoners in gilded cages—as the dynasty's approach to power transfer evolved over centuries. This transformation from violent competition to institutionalized confinement reveals much about the empire's changing character and the price paid for political stability.

During the empire's ascendancy, Ottoman princes received education befitting future conquerors. Young princes were not merely scholars of abstract principles but apprentices in the practical arts of governance and warfare. By their teenage years, many had already witnessed battlefield carnage, felt the weight of provincial administration, and learned to navigate court politics.

This system produced formidable rulers like Mehmed the Conqueror and Suleiman the Magnificent, whose early exposure to military campaigns and administrative responsibilities forged the leadership qualities that would define their reigns. Each prince, knowing the throne was attainable regardless of birth order, strove to distinguish himself in the eyes of the military, bureaucracy, and general populace.

Imperial tutors, often selected from the empire's most accomplished scholars and statesmen, guided these young men in subjects ranging from Islamic jurisprudence to military strategy. The princes' education culminated in appointments as provincial governors, where they established miniature courts that served as proving grounds for their leadership abilities.

The absence of primogeniture—the automatic succession of the firstborn—created a system where merit theoretically determined succession. In practice, however, it unleashed devastating fratricidal conflicts. Upon a sultan's death, brothers transformed into mortal enemies, each knowing that defeat meant not merely disappointment but execution.

The succession crisis following Beyazit II's reign exemplifies this brutal tradition. His sons Ahmet, Korkut, and Selim began positioning their forces and supporters even as their father still occupied the throne. Selim, demonstrating the ruthlessness that would later earn him the epithet "the Grim," not only defeated his brothers but forced his own father's abdication. Rumors persisted that Beyazit's suspiciously timed death during his journey into exile came by his son's command.

These succession struggles, while ensuring capable leadership, extracted a terrible price. Each new sultan's reign began with the execution of brothers, nephews, and sometimes even sons who might pose future threats. The practice reached its gruesome apex when Mehmed III ordered the execution of nineteen of his brothers upon ascending the throne in 1595, their coffins reportedly arranged by size.

The traumatic spectacle of royal fratricide eventually proved too much even for the hardened Ottoman court. The decisive break came during the reign of Ahmet I, who could not bring himself to order the execution of his mentally unstable brother Mustafa. Instead, he established a precedent that would transform the lives of Ottoman princes for generations: the kafes hayatı, or "cage life."

Rather than being killed, royal males not on the throne were confined to the palace Harem, living in closely guarded luxury but denied freedom, experience, or meaningful power. The "cage" was not a literal cage but a suite of rooms from which princes could not leave without permission, their movements and contacts strictly controlled by eunuchs and palace officials.

Life in the kafes fundamentally altered the development of Ottoman princes. Instead of leading armies and administering provinces, these potential rulers now spent their formative years in the cloistered environment of the Harem. Their world contracted to ornate chambers, enclosed gardens, and the company of women, eunuchs, and carefully selected tutors.

The psychological impact of this confinement was profound. Many princes, knowing they might never rule or might suddenly be elevated to the throne after decades of isolation, developed various neuroses and eccentricities. Some became obsessed with obscure scholarly pursuits or crafts—one imprisoned prince became renowned for his skill in making bows and arrows he would never use in battle.

Others sought escape in the sensual pleasures readily available in the Harem, becoming addicted to alcohol, opium, or sexual excess. The intrigue-filled atmosphere of the women's quarters further complicated their existence, as mothers, concubines, and female relatives manipulated these secluded princes as pawns in their own power struggles.

While the kafes system succeeded in preventing fratricidal wars, it created a new problem: sultans unprepared for rule. When a prince finally emerged from confinement to assume the throne—sometimes after decades of isolation—he often lacked the fundamental skills of governance. Having never commanded troops, negotiated with foreign powers, or administered territories, these sultans were ill-equipped to manage an empire.

The consequences became increasingly apparent as the Ottoman Empire entered its period of gradual decline. Sultans who had known nothing but the Harem's confined world struggled to comprehend the complex military, economic, and diplomatic challenges facing their realms. Many retreated into palace life, leaving actual governance to their grand viziers and other officials.

This transfer of effective power from the sultan to his administrators marked a significant shift in Ottoman governance. The grand vizier, originally the sultan's chief minister, increasingly became the empire's de facto ruler. Capable grand viziers like the Köprülü family managed to maintain imperial stability and even achieve military successes despite the leadership void at the top.

The kafes system's evident flaws eventually prompted further evolution in Ottoman succession practices. By the empire's later centuries, the dynasty abandoned both fratricide and the strict kafes system in favor of a more predictable approach: succession by the oldest male in the direct line.

This final adaptation brought the Ottomans closer to European succession practices, eliminating the wasteful bloodshed of earlier eras while attempting to ensure more capable leadership than the kafes system provided. Princes received improved education and somewhat greater freedom, though they never returned to the practical training of the empire's early days.

The Ottoman approach to succession embodies the classic dilemma of autocratic systems: how to transfer power without destabilizing the state. From open competition among battle-hardened princes to the seclusion of potential heirs, each system solved one problem while creating others.

The kafes hayatı remains perhaps the most distinctive Ottoman solution to this eternal challenge—a uniquely institutionalized middle ground between execution and freedom that preserved lives while often diminishing their quality and potential. In the golden chambers of their confinement, these princes embodied the compromises and contradictions of imperial governance.

As the empire itself began its long decline, these isolated figures—educated in palace etiquette but ignorant of the world beyond, heirs to military glory they had never experienced—became unwitting symbols of an empire increasingly disconnected from changing global realities. The cage that preserved the Ottoman bloodline ultimately contributed to the stagnation of the dynasty it was designed to protect.

Tue, Mar 11, 2025 1:49 PM

Comments (Total 0)