- Binbirdirek Mah. Klod Farer Cad. Güven Apartmanı No:2/302 Fatih/İstanbul, Turkey

- Open 08:00-22:00: Monday - Sunday

- drop us an email info@istanbulguideservices.com

- 24/7 service +90 555 6022454

tags:

Daily Life in Ephesus

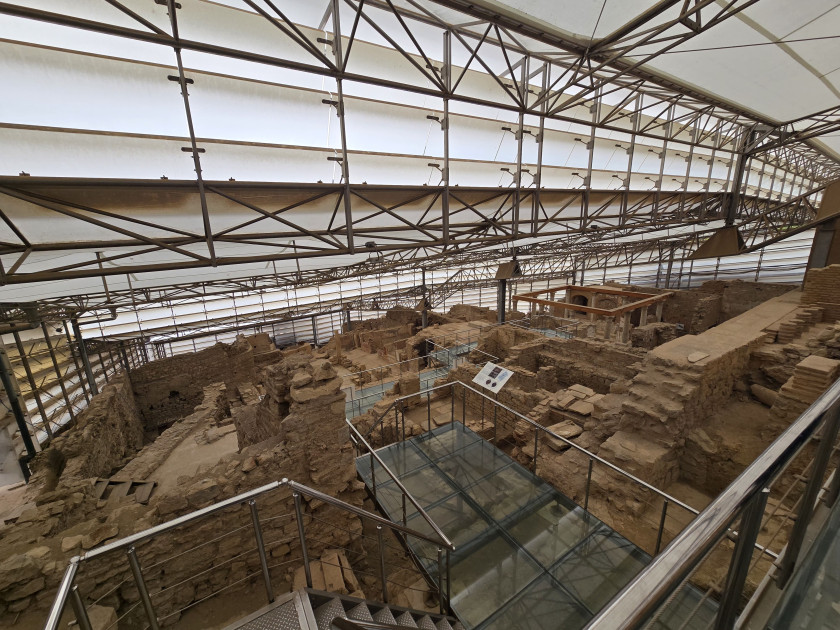

In the shadow of Mount Pion, nestled within the heart of ancient Ephesus, stands one of archaeology's most remarkable treasures: the Terrace Houses. These luxurious residential complexes, inhabited by the elite of Ephesian society from the 1st to the 7th century CE, offer a rare and intimate glimpse into the daily lives of wealthy citizens in one of antiquity's most prosperous cities. The exceptional preservation of these multi-storied dwellings has revealed not merely architectural brilliance, but the very fabric of domestic life during the Roman Imperial period.

Within ancient Mediterranean cultures, particularly in Ephesus, the concept of home transcended mere physical shelter, embodying profound spiritual significance. The family hearth represented the sacred center of domestic life, protected by Vesta (Hestia in Greek tradition), one of the most revered deities in the Roman pantheon. This goddess of the hearth flame embodied the continuity of family lineage and the stability of the household.

Daily rituals at the family altar included libations of wine poured onto the ground, the burning of fragrant incense, and prayers offered to household gods (Lares and Penates). These practices weren't merely superstitious gestures but fundamental expressions of Roman religious identity that bound families to their ancestors and to divine protection.

Within the spacious living quarters of the Terrace Houses, extended family units thrived across generations. The paterfamilias (family patriarch) wielded considerable authority, essentially deified within the domestic sphere. His role as guardian of family traditions, arbiter of disputes, and religious figurehead made him the living embodiment of the family's continuity and status.

Educational practices in Ephesus reflected the city's status as a prominent center of Hellenistic culture. Children's education began within the household, where they received instruction in basic literacy, numeracy, and civic values from parents or educated slaves. Around age seven, boys from wealthy families would begin attending formal schools or receiving instruction from private tutors in more advanced subjects.

The discovery of sculptures and artistic representations of renowned philosophers like Socrates and Plato within the Terrace Houses speaks to the intellectual aspirations of Ephesian elites. These weren't merely decorative elements but reflections of the homeowners' cultural values and philosophical affiliations. Such imagery established the family's connection to Greek intellectual traditions and signaled their refinement to visitors.

For adolescent males, education continued in the gymnasium—not merely a center for physical training but a complex institution for intellectual and civic development. Here, young men would study rhetoric, music, geometry, and other disciplines essential for participation in public life. The gymnasium at Ephesus, with its impressive colonnades and lecture halls, stood as a monument to the city's commitment to Hellenic educational ideals.

Music permeated daily life in ancient Ephesus, considered divine in origin and therapeutic in effect. Plato himself had argued that music could shape character, while Aristotle recognized its cathartic potential. Archaeological evidence from the Terrace Houses has yielded remnants of musical instruments and artistic depictions of musical performances.

The aulos (a double-reed wind instrument similar to an oboe), the kithara (a sophisticated stringed instrument), and the lyra (a smaller, more portable lyre) featured prominently in both private entertainment and religious ceremonies. Music accompanied symposia (drinking parties), religious processions, theatrical performances, and significant life events from birth to marriage to funeral rites.

Specialized rooms within the Terrace Houses, with their excellent acoustics and space for small audiences, suggest that musical performances were regular features of elite home entertainment. Music wasn't merely diversionary but served important social functions—demonstrating cultural sophistication and creating emotional connections during gatherings.

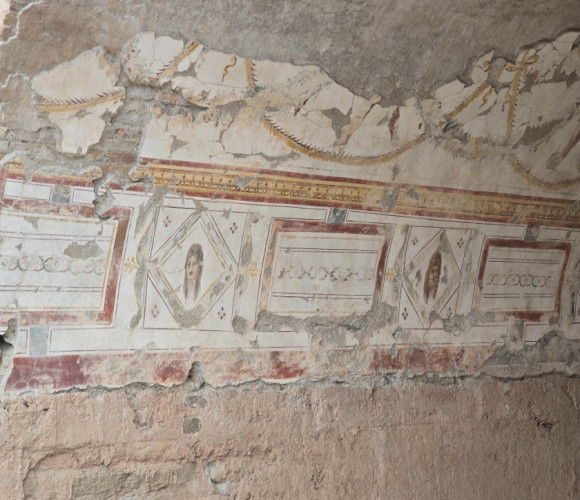

The triclinium (formal dining room) represented perhaps the most important social space within Ephesian homes. These rooms featured elaborate mosaic floors, frescoed walls depicting mythological scenes, and carefully planned dimensions to accommodate three dining couches (klinai) arranged in a U-shape around a central table. The practice of reclining while dining—with diners supported on their left elbow, leaving the right hand free for eating—was not merely a comfortable posture but a cultural statement associating the household with Greco-Roman sophistication.

The Mediterranean diet flourished in Ephesus, with locally abundant fruits forming dietary staples: grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives, and dates appeared regularly on Ephesian tables. The fertile lands surrounding the city produced grains for bread and porridge, while nearby pastures supported livestock including sheep, goats, and pigs. The proximity to the Aegean Sea ensured a steady supply of fresh fish and seafood, highly prized components of the elite diet.

Wine held particular significance, consumed at every meal by adults and considered essential for proper hospitality and religious observance. The vineyards surrounding Ephesus produced varieties acclaimed throughout the Roman Empire for their quality and distinctive character. Archaeological evidence from the Terrace Houses includes specialized wine storage areas and an impressive array of drinking vessels, from simple clay cups to elaborate silver kylikes (shallow drinking cups).

Olive oil served multiple functions in daily life. The highest grade oil was reserved for culinary purposes, while middle-quality oil might be used for personal grooming. The lowest grades found purpose as lamp fuel or for anointing athletes after exercise, highlighting the resource management practiced even within wealthy households.

While men of status divided their time between domestic responsibilities and civic engagement in the agora (marketplace and civic center) or baths, women oversaw the complex operations of the household. Evidence from the Terrace Houses reveals dedicated areas for textile production, where wool was carded, spun, and woven into fabrics for household use and sometimes for commercial purposes. These activities weren't merely domestic chores but expressions of feminine virtue celebrated in Roman cultural ideals.

The bath complexes of Ephesus, including the magnificent Scholastica Baths near the Terrace Houses, played central roles in daily social life. Here, citizens of various social ranks would gather not merely for hygiene but for exercise, conversation, business negotiations, and social networking. The elaborate bathing ritual—progressing from the tepidarium (warm room) to the caldarium (hot room) and finally to the frigidarium (cold room)—structured a significant portion of the day for many Ephesians.

Children's games in ancient Ephesus show remarkable continuity with play activities recognized today. Archaeological finds from the Terrace Houses include knucklebones (used in games of skill and chance), clay figurines, miniature furniture, dolls with movable limbs, and toy chariots. These artifacts suggest that childhood was recognized as a distinct life stage with appropriate recreational activities.

For adults, board games provided entertainment during leisure hours. Game boards carved into marble pavements in public spaces throughout Ephesus suggest the popularity of games like "Twelve Lines" (similar to backgammon) and various dice games. Gaming pieces carved from bone, glass, and semi-precious stones recovered from the Terrace Houses indicate that similar pastimes were enjoyed within the home.

The Terrace Houses of Ephesus stand as extraordinary testaments to ancient domestic life, preserving not merely architectural splendor but the intimate details of how people lived, worshipped, dined, learned, and played nearly two millennia ago. Through continued archaeological study of these remarkable structures, we continue to bridge the temporal gap between our world and theirs, finding both striking differences and surprising similarities across the centuries.

Mon, Mar 10, 2025 1:12 PM

Comments (Total 0)